Second Year History students studying the ‘Gender and Citizenship’ course curated a temporary exhibition on ‘Angry Young Men’ – the movement that spanned both literature and cinema in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Museum volunteer Emily Vine led a team of fellow students in this project and writes:

One of the reasons I’d chosen the Gender and Citizenship module was its use of the resources in the Bill Douglas Centre. As a regular volunteer I already had a good idea of how extensive the collection is, and how useful it could be to a module based upon nineteenth and twentieth century social history. I’d wanted to get involved in putting together an exhibition which was related to the module and was very pleased to have the opportunity of leading the group.

I was nonetheless apprehensive when we were told that the subject of the display would be British New Wave cinema; an area I was woefully ignorant about. Phil suggested we started by researching the subject in general, as well as the significant films of the genre and its leading stars. This research was particularly interesting, as it gave an insight into the earlier works and lives of actors who to me had always been old, such as the turbulent personal life of Richard Harris, who I will always know as kind, mild-mannered Professor Dumbledore.

After initial research, the group met to discuss possible approaches to our exhibition and titles for our display case. As last year’s group had focused upon female film stars (they looked at women and consumerism in the 1920s), we decided to concentrate upon the depiction of masculinity, and gave our display the snappy title ‘Angry Young Men.’

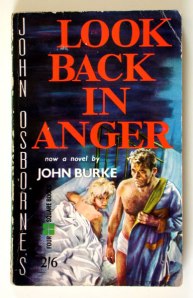

There were a number of items which we’d already looked at in seminars based in the BDC, so we selected those which were relevant to our subject of masculinity and continued searching the catalogue for more. We selected items from the archive on the basis of their relevance to the topic and visual appeal, and tried to utilise material which focused on some of the leading male actors of the genre, such as postcards of Laurence Harvey, Stanley Baker and Michael Caine. We also used fiction tie-ins of films such as ‘Look Back in Anger,’ ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’ and cinema publicity material to demonstrate the wide-ranging cultural impact of these films.

We had to accept that there was a lack of 3D items available; our subject matter did not really lend itself to figurines or other objects and the vast majority of our items were postcards, film stills, publicity leaflets and books. We also came across a number of interesting posters which we had to reject because they were just too large to fit in the display case. We did manage to find a good balance of colour items, and tried to make use of different levels to display the items in as aesthetically pleasing a way as possible.

My personal favourite items were the Daily Cinema cover depicting a still from ‘Room at the Top’ and the James Dean lobby cards, showing stills from ‘Rebel without a Cause.’ The bold red-pink colour and risqué nature of the image on the Daily Cinema cover makes it one of the most eye catching items; it gives an insight into how radical these films would have been at the time. The stills from ‘Rebel without a cause,’ although not directly linked to British New Wave cinema, work well in showing alternative contemporary depictions of disaffected youth in cinema and the influence of American popular culture on Britain. The immediacy of the threat of violence in these images and the use of vibrant colours is striking against the predominantly monochrome background.

Sophie Noke, another member of the team, writes about the social and historial background to the British New Wave:

The ‘Angry Young Man’ can be culturally constructed through the issue of ‘class’. Many of the characters we see in films might be considered to be a reflection of the writers who conceived of and invented the characters through their plays and novels; such as Alan Silitoe, Stan Barstow and John Osborne. During the 1950s and 1960s, the label became associated with young working-class or lower-middle class writers who were cynical about traditional British society and its obvious class distinctions, and we see this concept illustrated through various characters in films of the British New Wave. In films such asLook Back in Anger 1959, the issue of class is certainly prevalent; the ‘anti-hero’ Jimmy Porter (played by Richard Burton) is a quintessential example of an intelligent young individual whose opportunities were restricted due to his ‘lower’ social class. He demonstrates his angst towards society through lashing out at those around him, and through his turbulent relationship with his wife, Alison who comes from a wealthier middle-class family which Porter loathes. Although Porter has a university degree, he demonstrates the complexity of his character by choosing to work in the local market instead of aspiring to a well-paid job that might have been on offer to him. This has been said to demonstrate his hostility towards authority and the growing conservatism and class distinctions of 1950s Britain, although he feels unable to fight for his grievances or push for change. More widely, the struggles of post-war society are highlighted through the film’s rough, urban and claustrophobic setting, which helps to highlight the difficult reality of life for the under privileged classes.

These genres of films have been considered to encompass the theme of ‘kitchen-sink’ realism, portraying the typical domestic lives of the under-privileged classes or working class groups in poorer industrial areas such as the Nottingham depicted in ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’, or the Yorkshire of ‘Room at the Top’ and ‘A Kind of Loving’. Typical ‘gritty’ relationship dramas might take place in the confines of a small urban house or in a local pub environment which includes copious amounts of drinking and themes of social alienation. The legacy of the ‘kitchen-sink’ drama is seen in Soap Operas today in the twenty first century such as Coronation Street and East Enders, which in turn explore similar themes within a similar environment as the traditional 1950s British New Wave Dramas.