In the obituary of Jean Vigo in 1934 it was stated that he was to be missed “not just as a director but as a poet of living images”. Indeed, Vigo is commonly associated with the poetical. The dream-like images of his work reflect the introspective thoughts of his characters and it is for this reason that I am so drawn to his works. Although the plots of Vigo’s films centre on socio-political themes, the ways in which they are captured speak to another place in which the unspeakable is demonstrated. The Bill Douglas Centre has a number of pieces of original French publicity material, as well as books on the work and life of Jean Vigo, largely within the Roy Fowler collection.

Despite Vigo’s critical standing in the film world today, at the time in which they were released, they bore little consequence to the development of a French cinematic voice. Vigo died suddenly in 1934 after having contracted TB during the filming of L’Atalante on the French waterways. It is only since the French new wave that Vigo’s authority has truly been felt in the film world after his works influenced François Truffaut’s cinematic vision. During his short life, Vigo made four films, only one of which was a feature length production. Indeed, whilst L’Atalante (1934) is perhaps his best remembered film, Taris(1930), A Propos de Nice (1931) and Zero de Conduite (1933) also feature his trademark poetic realist style, which highlights how the socio-political environment affects the individual. Poetic realism is further characterised by the way it reframes real situations through a stylised cinematography. For example, L’Atalante is constructed of both a linear narrative and the non-narrative dreams of the characters. When the central figure searches for his wife, he dives into the river. Through the water, his wife’s image is superimposed. Manipulating reality as we know it, poetic realism predominantly depicts individuals who live on the margins of society, contained by a fatalistic viewpoint.

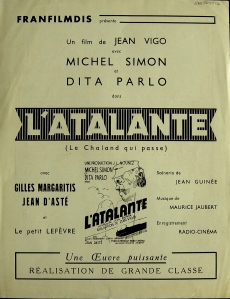

L’Atalante publicity sheet EXE BD 49766

Whilst the majority of critical readings situate Vigo’s use of poetic realism as a tool which undermines the French social elite, the style also represents his own search for a new cinematic voice. Vision and looking are prime characteristics of the works of Vigo and poetic realism enables him to affect the world depicted on-screen through the manipulation of cinematic techniques. Looking at the world in this way, the audience is faced with an alternative image of the place in which they exist.

Taris, Vigo’s first film, portrays celebrated French swimmer Jean Taris. Despite his social standing, it is only when viewing the underwater shots that the audience is able to consider Taris as he truly is. Whereas the interior scenes are focally restricted within the building, underwater space appears without end, allowing Taris complete freedom in his movements. Unlike the world above, the water is an area which encourages the introspective meditation Vigo hunts for through his cinematic voice. Whilst Vigo’s world topples the reality around us, it also deconstructs cinema as a technical form. Searching for a new way in which to represent the world, Vigo displaces film as a literal art form, employing montage and superimposition to reconstruct reality. Vigo also unsettles the cinematic ‘fourth wall’, allowing Taris to look directly into the lens. By doing so, Taris interacts directly with the audience and suggests that cinema is characterised by one’s personal response to the images on-screen. As we look into the lens, we are met not with an all-encompassing truth but rather, a reflected image of our own humanity.

Whilst Taris represents the stylised reality of a real person, Vigo’s only feature L’Atalantedepicts a largely realist portrait of a newly married couple. Despite this, Vigo’s method of filming the narrative captures the young, tempestuous love of the couple within poetics.L’Atalante is characterised by restricted vision. Not only does the watery setting perpetuate this by seeming to continue without end but also, it emotionally distances Juliette, the young bride, from her husband, Jean. Whereas Jean is most comfortable on the boat, Juliette’s discomfort on the barge is dominant within the narrative, affecting the emotional core of the film. Whereas the water served as a site of unencumbered freedom for Taris, in Juliette’s mind, the inability to define a static land mass represents the aimlessness of life on the boat. Although reluctant to admit it, Jean soon realises that Juliette’s presence is integral to his sense of self. Vision is also rooted in Vigo’s camera. In L’Atalante, we do not directly see Jean and Juliette’s world through the camera lens. Instead, the camera becomes an unseen character, following the narrative from a distance. Vigo’s lens is also meandering, epitomising Jean and Juliette’s search for identity in its pursuit for meaning through images. The camera exists in a ‘non-place’ and yet entirely defines how the audience perceives the material world.

Images from Taris in The Complete Jean Vigo Screenplays EXE BD 38271

L’Atalante lobby card EXE BD 49763

Vigo’s camera in A Propos de Nice, a short documentary film, is characterised by the same rootlessness as that of L’Atalante. Whereas L’Atalante depicts the introspective crises of the central characters, in A Propos…, Vigo uses the camera to accentuate his own social commentary. Focusing on middle class tourists, the film portrays the bourgeoisie as living without aim. Following the curved shapes of Nice’s municipal buildings, the camera is aesthetically giddy, void of a fixed point. Whilst much of the content is seemingly innocuous, Vigo’s use of montage contains an acerbic wit by positioning the holiday makers alongside wild animals. Indeed, it has been suggested that the film “not only condemns a particular social situation and its values but also calls […] for an overthrow of the society itself” (Marina Warner, 12).

Zéro de Conduite lobby card EXE BD 49760

Zero de Conduite similarly addresses the repositioning of society, depicting a boarding school as a microcosm for society at large. Anticipating Lindsay Anderson’s If (1968), the film follows a group of young boys as they plot and stage a pillow-fight coup, overthrowing their disciplinarian school masters. Highlighting the air of anarchy, the film rejects the singular character studies of Taris and L’Atalante, and instead focuses on shifting points of view. Real space is deconstructed and repositioned by the alternation of over-head shots and ground-level scenes. The world in Zero de Conduite is unsteady; there is no stable place in which the audience can focus as there is no consistency to the boys’ lives. All of Vigo’s films demonstrate his attempts to define the visions of his characters. In his works, the protagonists try to reappropriate the space around them for their own needs. Despite this, his spectre remains beneath the surface of his films and as his characters search for meaning, so too does Vigo. Despite his short cinematic career, it is apparent that, had he continued to work, Vigo would have shown much more of himself through the images of his films.